Scientists in Switzerland have taken a closer look at hand hygiene compliance in veterinary practices and veterinary clinics in a new observational study.

We regularly hear about new hygiene scandals and hospital infection figures related to human medicine. However, the infection prevention also plays a vital role in veterinary medicine and is increasingly becoming the focus of research and science. Analogous to human medicine, nosocomial infections in veterinary medicine primarily lead to additional patient suffering and a delay in the healing process of pets and livestock.

There are additional costs for the treatment of the infection. It becomes particularly challenging when antibiotic-resistant pathogens are in the mix and complicate the therapy of the infection in a complementary way. This is a real and growing concern. According to Swedish researchers, up to 18 percent of all employees in veterinary medicine are carriers of resistant bacteria. [1]

This is a problem that has been a topic of interest for decades. In 1979, among others, S. Bech Nielsen pointed out the importance of preventing nosocomial infections in veterinary medicine. [2]

In 2013, a group of U.S. researchers identified that nosocomial infection rates in veterinary hospitals were higher than 10 percent. [3] Animals that had undergone surgery and had a urinary catheter inserted were particularly likely to be infected.

Nothing as effective as good hygiene

To deal with this recurring problem, how can infections be most effectively prevented in veterinary medicine? The research shows that careful hand hygiene is key. Hand disinfection practices from hospital-settings should be mentioned here. The World Health Organization (WHO) calls hand hygiene “the most important measure to reduce infections.” [4]

From human medicine, we are all familiar with the established model of the 5 Moments of Hand Hygiene, launched by the WHO in the first decade of this century and implemented by numerous national campaigns since then. The model lists the triggers for hygienic hand disinfection in hospitals. These five categories make hand hygiene rules clear and simple for hospital staff. Hands who been disinfected:

- before patient contact

- before aseptic procedures

- after contact with potentially infectious material

- after patient contact

- after contact with the immediate patient environment

Based on this concept, Swiss researchers recently conducted a comprehensive observational study focused on hand hygiene compliance in veterinary practices. To do so, the researchers adapted the 5 moments of hand disinfection to the realities of veterinary medicine.

Hygiene in Veterinary medicine: hand disinfection still has room for improvement

From September 2018 to May 2019, a total of seven veterinary facilities in Switzerland participated in this study. The researchers identified 2,056 moments in which hand disinfection had been necessary and noted whether or not hand disinfection had actually been carried out in these situations. To do this, a trained person observed the staff in the veterinary clinics.

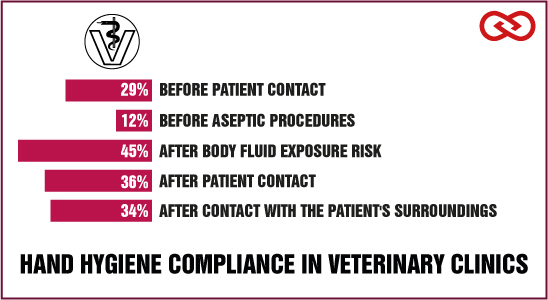

The results show that hand disinfection took place in only 32% of all required cases. Hand disinfeciton before aseptic activities—probably the most important indication from an infection perspective—fared the worst with a compliance rate of 12%. This disparity is consistent with previous studies on hygiene in veterinary medicine. [5]

The authors even investigated how hand hygiene behavior varied across the different premises of a veterinary practice or clinic. Here, the meeting room scored best with a hand hygiene compliance of 42 percent, whereas in the pre-operation room only every fifth hand disinfection is performed.

Make disinfection dispensers accessible, give feedback, and deliver training

The results found in the Swiss study underscore that hygiene in veterinary medicine still has great potential for improvement and is roughly on par with human medicine in terms of hand disinfection behavior. In hospitals, hand hygiene compliance ranges from 30-50%, depending on the type of ward, according to experience. [6]

The fact that the disinfectant dispenser is visited more frequently after patient treatment than before animal contact is, for the scientists, once indication that hand hygiene by medical staff is more for self-protection.

According to the study authors, concrete approaches to improving infection control in veterinary clinics and practices require implementing a multimodal strategy. This includes regular and consistent hand hygiene training for staff, optimizing the location and number of hand sanitizer dispensers, and consistent feedback to staff regarding hand hygiene behavior.

We conclude this article with a figure that should illustrate the great importance of veterinary medicine as a component of medicine: According to the German Veterinary Association, there are more than 12,000 veterinarians in Germany alone today—and the number is rising. [7]

Study:

Schmidt JS, Hartnack S, Schuller S, Kuster SP, Willi B. Hand hygiene compliance in companion animal clinics and practices in Switzerland: An observational study. Vet Rec. 2021;e307.

Sources

[1] Grönlund Andersson, Ulrika, et al. “Outbreaks of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among staff and dogs in Swedish small animal hospitals.” Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases 46.4 (2014): 310-314.

[2] Bech-Nielsen, Steen. “Nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infection in veterinary practice.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 175.12 (1979): 1304-1307.

[3] Ruple-Czerniak, A., et al. “Using syndromic surveillance to estimate baseline rates for healthcare‐associated infections in critical care units of small animal referral hospitals.” Journal of veterinary internal medicine 27.6 (2013): 1392-1399.

[4] World Health Organization (WHO) “WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care: a summary.” Geneva: World Health Organization 119.14 (2009): 1977-2016.

[5] Smith, Jo R., Zoe R. Packman, and Erik H. Hofmeister. “Multimodal evaluation of the effectiveness of a hand hygiene educational campaign at a small animal veterinary teaching hospital.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 243.7 (2013): 1042-1048.

[6] Erasmus, Vicki, et al. “Systematic review of studies on compliance with hand hygiene guidelines in hospital care.” Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 31.3 (2010): 283-294.

[7] Bundestierärztekammer – Statistik 2020: Tierärzteschaft in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (2020).

Kommentieren